“Man is not going to wait passively for millions of years before evolution offers him a better brain.” – Dr. Corneliu E. Giurgea

No. Man is not.

Because Man needs better brain NOW.

And he’s needed better brain NOW since, presumably, the beginning of human history. Heck, perhaps even before documented history, considering how deeply ingrained our attraction towards mind-altering substances is. Regardless, judging by the amount nootropics that have popped up in recent years versus the ones that have always been around, the relationship between people & nootropics seems to encompass a long, deep history that has changed just as much as it’s stayed the same.

The TL;DR Version: Enhancing cognition is a prehistorically old tradition, meaning that it’s a tradition that predates the historically concept of “traditions,” despite the relatively new concept of “nootropics.” In this history guide, I cover the use of what we today call “nootropics” from pre-history to today.

Page Contents

Discovering Nootropics

When Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s father took him to “discover” ice in the opening passages of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the comedic irony of the scene revolved around the fact that ice not only had already been discovered, but had existed looong before its introduction to the citizens of Macondo.

In Buendía’s world & in ours, the “discovery” of ice didn’t coincide with the invention of ice, but rather the recognition of ice’s usefulness.

Likewise, nootropics have existed looong before their “discovery”–yet, unlike ice, the recognition of nootropics’ usefulness did coincide with the invention of a nootropic, which was actually the first nootropic to receive the name “nootropic”: Piracetam.

Initially developed in 1964 by Romanian psychologist & chemist Corneliu E. Giurgea to treat motion sickness, Piracetam was quick to demonstrate its benefits on mental performance, memory consolidation, & information processing–benefits that were entirely unique to any lab-synthesized substance at this point in time. Consequently, Dr. Giurgea used Piracetam as a model with which to establish the criteria of what constitutes a nootropic, including:

- Enhancement of learning acquisition

- Resistance to disruptive mental conditions

- Facilitation of neuronal transfer of information

- Enhanced resistance to physical & chemical brain injury

- Increased tonic cortico-subcortical control mechanisms

- Absence of usual pharmacological side effects of neuropsychotropic drugs

Under Dr. Giurgea’s criteria, a true nootropic not only enhances cognition, but possesses a degree of brain-protective elements–or, the more inclusive interpretation: It doesn’t harm the brain while enhancing cognition.

With these rules laid out, it didn’t take long for the newly defined nootropic list to fill up, considering the amount of natural herbs, vitamins, minerals, & compounds we’ve already been consuming for the sake of brain health. In fact, the practice of supplementing nootropics has looong predated their discovery, linking several so-called nootropics well before the latest ice age.

The Pre-History of Nootropics

While our understanding of nootropic history is limited to… well, history–i.e. the documentation of humankind–there are natural nootropics believed to have their beginnings prior to recorded human civilization.

For example: Ginkgo biloba.

Referred to as a “living fossil,” Ginkgo trees have existed for over 200 million years, dating to the days of dinosaurs, with some individual specimens found to live up to 3,000 years. As such, Ginkgo’s brain benefits presumably existed before benefiting brains.

Other examples of herbs & substances that qualify for this list:

- Bacopa monnieri

- Carmellia sinensis (green tea)

- Ashwagandha

- Rhodiola

- Eleuthero

- Ginseng

- Lion’s Mane

As well as various brain enhancers such as Fish Oil, Vinpocetine, Huperzine-A that exist in the natural world, yet require extraction methods of the modern era to achieve their nootropic potential.

However, this isn’t to say that such natural nootropics weren’t used by prehistoric humans:

South American tribes chewed & brewed coca leaves (cocaine alkaloid) for energy & alertness.

Pacific ceremonies supplied Kava Kava drinks for mood & socialization.

Native Americans notoriously consumed peyote for its “spiritual” hallucinogenic properties, which were later condemned by Spanish conquerors as “satanic trickery.”

Even caveman “rock art” is believed by many to have been influenced & inspired by mind-altering substances, many of which aren’t necessarily considered “nootropic” (at least by Dr. Giurgea’s criteria), but nevertheless may suggest of an early proclivity towards manually altering mind status among humankind.

With that in mind, the capacity for using mind-altering substances, and perhaps, in certain cases, even revering these items as something spiritual, was, and continues to be, an important facet of the human experience.

Early Records of Nootropic Usage

Here’s where the history of nootropics gets a little more concrete.

Because we actually have tangible history to discuss here.

Naturally, most nootropic herbs were either chewed or brewed throughout the early centuries of human civilization. And this seemed to be the case well up until modern pharmacies began transforming leafy teas & roots into capsulated pills (yet, even today nootropic options like green tea are still more popular than, say, L-Theanine extract).

![First page of The Classic of Tea. By Lu Yu (my book) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nootropicgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/classic-of-tea-232x300.jpg)

- The History of Tea

- Key Figures in Tea Lore

- Tea Etiquette

- Tea Equipment

- Tea Agriculture

- Tea Tools

- So on and so forth…

Today, we typically classify teas (namely green tea) as energizing relaxers. But for Lu Yu, tea symbolized physical & metaphysical harmony. Tea symbolized the unity of the universe.

And this spiritual element to tea drinking wasn’t unique to Chinese culture.

In the Vedas (Sanskrit for “knowledge”), the oldest segment of Sanskrit literature and Hindu scripture, ayurveda medicine was founded–which accounts the transmission of knowledge from the Gods to the sages to the physicians. For more than 2000 years, ayurvedic practices have varied, typically centering on herbal mixes for teas, powders, & spices. Ayurvedic nootropics (or Medhya rasayana) include Bacopa monnieri, Ashwagandha, Intellect plant (Celastrus paniculatas), and more…

The primary goal of ayurveda: Swaasthasya Rakshanam–or the preservation of health for longevity & vigor.

![By HPNadig (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nootropicgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Dhanvantari.jpg)

Following the Enlightenment of the Western world, nootropic herbs & compounds were viewed, more or less, in increasingly secular terms, in an increasingly scientific language that foretold of the rapid acceleration of science & invention in the 19th century.

Turn of the 19th c. Nootropics

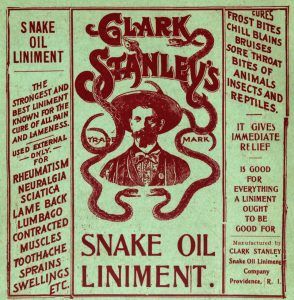

One of the most common insults used against the supplement industry is “snake oil”–this, of course, in reference to the “Snake Oil Salesmen” of the late 1800’s & early 1900’s.

I can’t help but to laugh at how the last section ended with “science & invention” to be followed up by a description of snake oil, which was entirely invention, but zero science. Yet, to be fair, it was a sham invention that was playing off of the exciting medical science of the time.

Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment, the fraudulent snake oil that was proven ineffective by the U.S. government in 1917, didn’t contain actual snake oil, but rather:

- Mineral oil

- Beef fat oil

- Red pepper

- Turpentine

- Camphor

Ingredients that it would be a stretch to label as “Cure Alls,” and that definitely did not provide the cognitive “Brain Tonic” advantages advertised on several sham snake oil species.

Ingredients that it would be a stretch to label as “Cure Alls,” and that definitely did not provide the cognitive “Brain Tonic” advantages advertised on several sham snake oil species.

Likewise, Confederate colonel John Pemberton’s Coca-Cola, which was initially sold as a coca wine to substitute the inventor’s morphine addiction, also provided questionable cognitive benefits due to the nerve tonic‘s notorious reliance on cocaine & caffeine for energy.

Upon discovery of cocaine’s risk of abuse, Coca-Cola was removed of its coca content in an attempt to make it healthier for the body & brain. Now, the drink is almost entirely sugar & caffeine, which… I guess qualifies as improvement?

The Green Revolution

Not to be confused with the later push towards organics (which was in large part a response to this movement), the Green Revolution refers to the early-to-mid 20th century set of research & development in the field of agriculture that produced a range of new techniques that both: A) Yielded unprecedented crop levels, and B) Introduced unprecedented levels of change in the ways food is produced. Change that is heavily criticized today for its use of harmful pesticides & controversial GMO tactics. Even so, the change brought on by the Green Revolution not only increased crop levels, but yielded more resources for nootropic experimentation that was just on the horizon, as well as introducing new methods of extracting natural bio-active compounds from organic sources to increase effectiveness of herbal nootropics.

1960s Nootropics in Russia (USSR)

If we’re being technical, the 1960’s marked the true start of nootropic history.

Or at least the start of the concept of nootropics.

As I already covered, the first nootropic, Piracetam, was invented in 1964 by Romanian chemist Dr. Corneliu E. Giurgea, leading to the “discovery” of nootropics as a class of consumables. Upon observing the safe brain-enhancing effects of Piracetam, Dr. Giurgea devised the nootropic criteria list with which to guide the development of later Racetams.

Yet, despite the drugs’ origins in Belgium, Racetams are most often associated with the Soviet Union. Following the groundbreaking developments of Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov’s conditioning research, coupled with the pressure to compete with the capitalist pigdogs opposite of the Cold War, the USSR was investing in techniques to optimize the mind, that practically bordered on mind control.

Okay, let’s be honest: It was mind control they were after.

![Portrait of Ivan Pavlov, frustrated, because. Mikhail Nesterov [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nootropicgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Ivan-Pavlov.jpg)

Not all herbs that are considered adaptogenic are necessarily nootropic, but the key characteristic of adaptogens is inherently beneficial to the brain & cognition: Improvement of the body’s ability to adapt to stress.

![Subarctic Rhodiola enjoying a view. By Gérald Tapp (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nootropicgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Rhodiola_rosea-201x300.jpg)

- An adaptogen should cause minimal harm to the body.

- The action of an adaptogen should be non-specific in its range of anti-stress benefits.

- An adaptogen normalizes bodily parameters against pathological conditions.

If the aforementioned nootropics (namely Racetams) were explored for the sake of mind control, then adaptogens (e.g. Rhodiola Rosea, Panax Ginseng, Eleuthero) were researched for bodily control–namely for important Soviet figures such as Olympians, bodybuilders, cosmonauts, politicians, scholars, and even the researchers themselves.

Unfortunately (for the USSR), none of the nootropics nor adaptogens proved effective at accomplishing mind control… But, fortunately (for the rest of the world), research on nootropics & adaptogens helped pioneer a category of supplements that turned out to be very, very healthy for the mind.

Psychedelics, Psychotronics, & the Mystical Oneness

There isn’t a sexier (or is it psexier?) time in nootropic history than the 1960s. Not only was the first nootropic “discovered” during this time, but other mind-altering substances were making waves across the Western world. Naturally, with the rise & resurgence of marijuana, LSD, shrooms, & other illicit substances, coupled with the “Turn on, Tune in, Drop out” philosophy of San Francisco’s counter-culture, “mind-altering” nootropics spiked plenty of controversy, worry, & doubt in mainstream society.

Toss in the fact that the concept of nootropics originated from across the Iron Curtain, from the Soviet Union, who later were believed to be experimenting in so-called “Psychotronic Warfare”–weaponry & tech designed for mind control–and it becomes easy to imagine why nootropic drugs (e.g. Racetams) were approached with a heavy dose of skepticism.

Of course, while it was later revealed that the Soviets were conducting psychotronic experiments, the U.S.’s Project MKUltra, a CIA branch dedicated to psychotronics, was also exploring drugs & substances in an effort to seize control of the mind. So if you’re still wondering if the hippies were onto something with their whole “mystical oneness” ramblings, there’s your answer.

1970-80s Nootropics

Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, nootropic development more or less followed the same trajectory laid out in the 1960’s. The USSR continued research on nootropics & adaptogens, inspiring both sides of the Soviet-American Arms Race to find new meanings of the mind. Meanwhile Western culture was falling deeply in love with computers and (not coincidentally) cyberpunk transhumanism—the belief that humans can evolve beyond their current physical and mental limitations, particularly by means of science & technology (more on this in a bit).

This was also when the term “nootropic” entered the mainstream after Dr. Giurgea officially coined it in 1971, stemming from the Greek “noos” meaning mind and “tropein” meaning towards or to bend (as in mind-bending).

Notable nootropic drug entries during this time period:

- Aniracetam

- Oxiracetam

- Pramiracetam

- Phenylpiracetam

- Nefiracetam

- Pikamilon

- Phenibut

- PRL-8-53

While distrust against the government & the “Man” somewhat simmered throughout the ’70s mainstream, there still existed a hip attitude against political & corporate powers that manifested itself in Do-It-Yourself (DIY) fashion:

- The DIY Movement of the ’70s operated via self-reliant mimicry. It was a punk ideology that imitated higher structures on its own term. For example, consider punk music itself: The ’70s punk rocker rejected consumer culture by creating music without professional equipment, playing in unprofessional environments, to rowdy crowds of unprofessional listeners. The music was still a commodity to be consumed, but it was a commodity that operated on its own terms. It did it itself.

![By Plismo (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nootropicgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Ramones_Toronto_1976.jpg)

And in hacker culture, most notably in cyberpunk communities, the hacker took modern tech of the time and manipulated it to perform at higher levels. In pop culture, this was represented through fictional high-tech “garage shop” inventions (e.g. Back to the Future‘s DeLorean turned time-machine). In biology, this concept was explored through nootropics, which were essentially viewed as biohacking tools for the mind.

Because, after all, the mind is essentially an organic computer, right?

At least that was the growing consensus by the late 1980’s as questions of humanity surfaced in light of the growing potential of sentient cyber operating systems. Thus, if it were possible to upgrade an OS system, then nootropic transhumanism should theoretically also be possible.

As such, if the 1960s were about rejecting the outward machinations of reality for the inner meanings of life, then the ’70s, and, even more so, the ’80s, were about understanding the inner machinations of humankind and hacking them to achieve outward transcendence.

For 80’s biohackers, nootropics became a symbol of self-reliance. Nootropics were a means of achieving increased brainpower without having to submit to the pharmacies of all those lame-O greedy squares in higher offices.

An ironic achievement considering nootropics’ conceptual origin by the biggest lame-O square of them all: Government.

Turn of the 20th c. Nootropics

On December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union was dissolved.

![By NASARestoration by Adam Cuerden [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nootropicgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ASTP-crew-300x240.jpg)

And just in time as the Western world was finally getting around to figuring out how to regulate (or rather how to not regulate) the drugs & supplements that accumulated over the past century.

While the legality of nootropics vary by each government, the general system upheld by most countries were (and, for the most part, still are) as follows:

- Nootropic Drugs – Require government regulation to be legally sold for consumption. Depending on the drug’s schedule (i.e. risk of abuse), the government may or may not control access to the drug (via prescription).

- Dietary Nootropic Supplements – Essentially a sub-category of food that is “innocent” until proven “guilty” in terms of health & legal status.

This was an important & necessary legal distinction considering the rise of pharmaceutical cognitive-enhancers (or “smart pills“–Adderall, Ritalin, Vyvanse, etc.) during the turn of the 20th century. Particularly where nootropic drugs (e.g. Racetams) are concerned, there exists plenty of confusion regarding the difference between smart pills & nootropics. And in an effort to thwart abuse of prescription smart pills, often times governments drag down harmless nootropics with their food & drug politics.

This becomes an increasingly difficult issue as more & more manufacturers are finding ways to extract lab-synthesized compounds out of organic substances. Depending on where you live, semi-synthetic compounds such as Huperzine-A or Vinpocetine may be legal for recreational use or barred by prescription.

Even so, today, both ends of the nootropic spectrum have arguably been fulfilled: We now have intense pharmaceutical cognitive enhancers and natural, brain-healthy nootropics. Compound that data (and stack those brain boosters) with the energy drink craze of the past couple decades, and it seems we’re currently living in an era of healthy, yet dopamine-flushed brain tissue & pounding caffeinated hearts.

Nootropics in Pop Culture

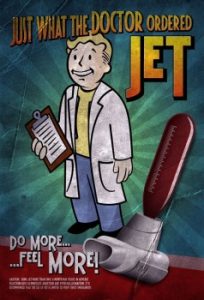

In recent years, the popularity & abuse of prescription-based uppers has garnered major interest in quote-unquote “smart pills.” Naturally, with the rise of these pharmaceutical-grade cognitive enhancers came a mix of fiction that both cautioned against & relished in nootropic culture–starting with Aldoux Huxley’s Brave New World soma pills, A Clockwork Oranges’ Moloko Plus, Equilibrium‘s Prozium, Fallout‘s Jet, continuing through the 2011 movie Limitless, which features NZT-48, a fictional pill that unlocks the brain’s full potential.

Due to the success of the latter, many recent supplement companies have transformed what was initially intended as a cautionary tale against our “Adderall age” into a selling point, labeling their focus driven products with shameless titles such as The RealNZT, Neuro-NZT, etc. etc. Even though such a thing doesn’t exist.

And again, we’re back to illicit “mind-altering” substances muddying our perceptions of true nootropics that enhance brain health. Although, with the rise of articles like this and readers like you, I can’t imagine we’re too far off from finally getting nootropics right… At least until the next drug craze closes (or opens?) our doors of perception, again.

Conclusion

Despite its cognitive effects, I don’t consider caffeine a true nootropic.

Yet, when I witness, on a daily basis, the grasp the drug has on us, the borderline spiritual aura imbued in a cup of coffee, I can’t help but to marvel how far we’ve traveled only to stay in the same place we were thousands & thousands of years ago.

True: Modern science has taken us to a point that has made nootropics work better than ever before, due to major developments in concentrated extracts, bio-compound synthesis, standardized forms, research-backed stacks, etc., etc. And thanks to modern science, we’ve realized that some brain health techniques are completely bad ideas (such as drilling holes in skulls to release the medieval demons).

Even so, the motivations & meanings underlying these nootropic developments are damn near carbon copies of their ancestors, except with different names & nationalities to stand by.

Raising the question: Are we truly progressing or simply, perpetually rediscovering ice?

Read my Best Pre-Made Nootropic Supplements list here.